University of Bristol scientists discuss exciting new pathway to target macular degeneration

University of Bristol researchers, Dr Jian Liu and PhD student Katie Cox, share their team’s ground-breaking discovery on the relationship between a key protein in our eyes and how its gradual reduction due to ageing impacts sight loss. Their findings may potentially lead to development of less invasive gene therapy treatments for patients with macular degeneration and other eye diseases.

Jian Liu has worked in the academic unit of ophthalmology at the University of Bristol for the past 13 years. With a background in micro and molecular biology, Jian chose to specialise in ocular immunology, and more recently, in dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The science:

"AMD is a very complex disease. There are many different disease pathways contributing to its development,"

says Jian. Most eye diseases develop indiscriminately, irrespective of age, gender, or ethnicity. But, in the case of macular degeneration, its common drivers are age-related changes to our immune systems and resulting chronic inflammation.

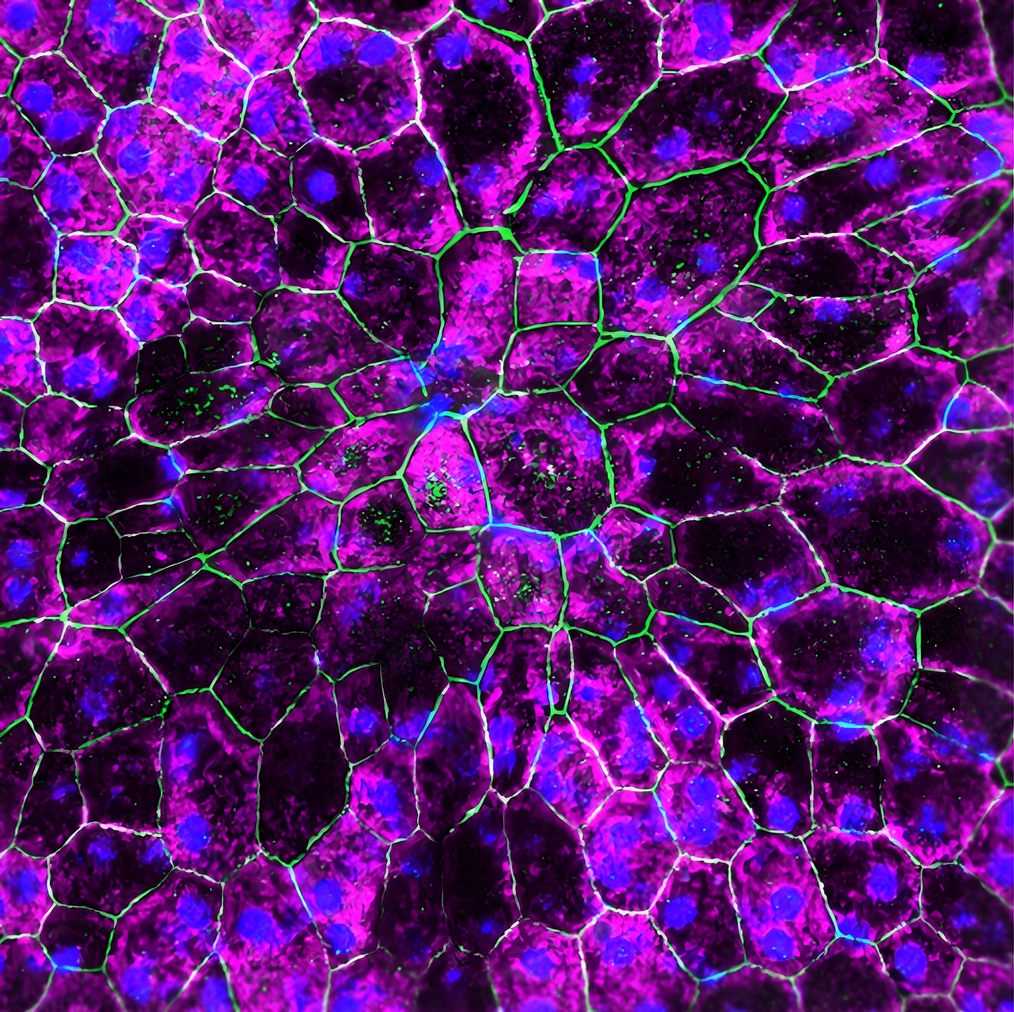

Jian and the Bristol team’s latest paper, which featured on the cover of Science Translational Medicine, identifies a mechanism by which this chronic inflammation leads to worsening vision as we age. And it is attributed to the presence of the protein "IRAK-M". This protein exists in a layer of cells at the back of the eye, called the retinal pigment epithelium. When the layer gets damaged, such as by inflammation, it can result in serious eye conditions and vision loss. The team found that IRAK-M plays a key role in retaining the health of the retina (and therefore our ability to see) as we age.

Front cover from June’s Science Translational Medicine showing rescued retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells following IRAK-M gene therapy. Credit: Liu et al./Science Translational Medicine

“We found IRAK-M reduction happened gradually during the ageing process. From twenty years old to eighty years old to one hundred years old, the curve is a gradual decrease,”

explains Jian, who was lead author on the research paper. His PhD student, Katie Cox, is a fellow collaborator on the project. Three years ago, she made the decision to move from neuroscience to ophthalmology, mostly out of curiosity in Jian’s area of research. “From a clinical perspective, something really interesting about the eye is that you can look in it with much greater ease than you can with the brain,” says Katie on her change of specialism.

The lab work:

To study ageing eyes, Katie and Jian spent hours upon hours in total darkness, conducting light induction experiments to measure retinas in animal models. Afterwards, they drew up thousands of lines and pictures of these retinas. But to grasp whether their findings of retinal degradation was also true for humans, Katie and Jian’s team needed to source existing clinical samples, which was not easy.

“It was difficult to obtain high quality samples, for example, from NHS transplantation laboratories. There is often a gap in time between collecting and the processing of samples,”

explains Jian. There were occasional long stretches of time waiting for useable data to come through. Also, the sheer scale of clinical samples needed was far higher than either Katie or Jian anticipated due to huge variations of samples from patient to patient. The team faced having to halt the progression of experiments, which frustratingly, risked delays to the entire project.

However, the researchers were able to find innovative solutions to work around these obstacles. To increase the sample size and quality of their data, they expanded collaborative links with international research groups.

“One of the major strengths of this project is that it’s got so many contributors with so many skill sets,”

says Katie, whose team partnered with scientists from the USA, Germany and Australia. They also found that they could generate data by themselves using a publicly available online database. “We used strengths of different groups to help overcome challenges in the research. It’s teamwork always,” adds Jian.

The results:

In diversifying and collaborating on their clinical samples, an exciting bigger picture began to emerge for the Bristol team.

“Research is like finding pieces of a puzzle. You get a little bit of euphoria when you find a piece that fits,”

says Katie. Researchers found clear indicators that the IRAK-M protein’s expression declines with age, and that decline is even more prominent in AMD patients compared with non-AMD patients of similar ages. They also named inflammation, caused by ageing and oxidative stress, as a key driver of the retina’s degeneration.

Now that they had several “puzzle” pieces, the team wanted to test whether changing levels of IRAK-M would have an effect in practice on animal models. Jian explains,

"Using a specific gene therapy approach, we found that we could increase expression of IRAK-M in the retina cells.”

By this method, researchers were elated to discover that they could reduce the effects of age-related damage to the retinas.

The current treatments:

Current treatment options for AMD patients are limited and invasive. With wet macular degeneration, patients need frequent injections into their affected eyes, as often as monthly or bi-monthly. “Hearing that patients with late-stage AMD have to have regular injections into the eye was a shock for me,” admits Katie. “Creating opportunities for patients to have other potential treatment options- treatments that work better or earlier- I think that’s very important.”

Research team with Jian Liu (centre left) and Katie Cox (centre right)

The proposed solution:

This Bristol team’s discovery has potential future applications to treat macular degeneration in a less invasive way than current offerings.

“Our strategy is gene therapy, which offers the potential for long-term effects with just one injection. Patients would only need one single injection, and after that the gene can express over time continuously in the eye,”

Jian explains. After seeing positive results in the animal models, the team want to further demonstrate the preclinical safety and efficiency of their gene therapy treatment, before undertaking clinical trials with people. Despite this project being in preliminary stages, the team hope to eventually have a viable treatment option for thousands of patients with macular degeneration.

Now, most sight loss treatments can only take place once damage has already been done to the eye. “We’re getting to a point of having to regenerate things or stop them getting worse. But we can’t give you that vision back,” explains Katie. The gene therapy solution that Bristol researchers are hoping to develop would give clinicians and patients a chance to spot the early warning signs in the retina before vision has a chance to deteriorate.

Katie, who finishes her PhD this year, believes that

“Sight is the sense we fear losing the most. Blindness is a major issue in the ageing population and clinically, it’s a huge burden, so to be able to make an impact is really exciting.”

Jian agrees. "As translational scientists, we are eager to address this extensive and significant burden and the challenges for our societies. We want to contribute to the fight for people's quality of life.”

Join our mailing list to stay updated on ground breaking sight research and developments.

The importance of eye research:

Sight loss and blindness pose an increasingly urgent threat to ageing populations worldwide, with cases of macular degeneration, glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy increasing across the board. AMD alone affects 200 million people globally and is projected to increase to 288 million by 2040. Jian adds,

“In the USA alone, there are about 11 million people affected by AMD, which is equal to all invasive cancers combined.”

Yet, ophthalmology continues to be a critically neglected medical area. Katie and Jian both feel this is due to the perceived lack of urgency around eye conditions. Sight loss can often get lost in the landscape of other critical diseases.

“Loss of vision is ironically less visible to other people. Whereas for things like Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, Parkinson's… people can see from the outside the impact that it's having.”

Jian points out that sight loss and blindness continue to be overlooked. “People think that eye disease may be less severe [than other diseases] because we can still survive. But sight loss or blindness is critical, it not only affects the patient- but it also affects everyone in their life.”

Jian and Katie’s research would not have been able to progress at this vital translational stage without funding. “We have substantial support from funders like Sight Research UK, our universities and our international collaborators, which is essential and important for the success of our research,” says Jian.

This research was funded by Sight Research UK; the Rosetrees Trust; Stoneygate Trust; Underwood Trust; Macular Society; Moran Eye Center and Sharon Eccles Steele Center for Translational Medicine (SCTM) at the University of Utah, USA, the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, USA and supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) BRC Moorfields and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology.